The Bounty of the Earth

Saturday, October 6, 2018 • 7:30 p.m.

First Free Methodist Church (3200 3rd Ave W)

Orchestra Seattle

Seattle Chamber Singers

William White, conductor

Catherine Haight, soprano

Brendan Tuohy, tenor

Ryan Bede, baritone

Program

William C. White (*1983)

Acadia Fanfare

Lili Boulanger (1893–1918)

Psaume XXIV (“La terre appartient à l’Eternel”)

Aaron Copland (1900–1990)

Suite from Appalachian Spring

— intermission —

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732 –1809)

“Autumn” from The Seasons, Hob. XXI:3

About the Concert

Our opening program celebrates the Earth itself as we begin a season-long focus on the work of Lili Boulanger with her taut, vigorous setting of the 24th psalm (“The Earth Belongs to the Eternal One”), featuring the Seattle Chamber Singers and Orchestra Seattle’s brass section. We then turn to one of the great American classics, Appalachian Spring by Aaron Copland (who was a student of Lili Boulanger’s sister, Nadia.)

The second half of the concert features a staple of the OSSCS repertoire: Franz Joseph Haydn’s The Seasons, a celebration of country living and harvest festivities. Audience favorites Catherine Haight and Ryan Bede join tenor Brendan Tuohy, making his OSSCS debut, for the autumnal portion of Haydn’s final masterpiece.

This concert begins a new chapter in OSSCS’s history, the inaugural program featuring recently appointed music director William White. Maestro White offers a musical introduction by way of his own Acadia Fanfare, an orchestral showpiece written to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Acadia National Park.

Join OSSCS music director William White one hour prior to the concert (at 6:30 p.m.) for a behind-the-scenes look at the music on this program.

About the Soloists

Soprano Catherine Haight appears frequently with the region’s most prestigious musical organizations, regularly performing in Pacific Northwest Ballet’s Carmina Burana and The Nutcracker. Reviewing PNB’s world premiere of Christopher Stowell’s Zaïs, The Seattle Times called her singing “flawless.” She appears as soprano soloist on the OSSCS recording of Handel’s Messiah, the Seattle Choral Company recording of Carmina Burana, and on many movie and video game soundtracks, including Pirates of the Caribbean, Ghost Rider and World of Warcraft. Recent concert performances include Dvořák’s Te Deum, Handel’s Israel in Egypt, and Bach’s Mass in B Minor and St. John Passion with OSSCS, Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915 with Seattle Collaborative Orchestra and Richard Strauss’ Four Last Songs at Seattle Pacific University, where she has served on the voice faculty since 1992. Learn more: spu.edu

Tenor Brendan Tuohy has been praised by The Cincinnati Post for his “big, bold tenor edged with silver.” This summer he returns to the Grant Park Music Festival to sing Haydn’s Theresienmesse, following a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in 2017. Recent operatic engagements include Tony in Bernstein’s West Side Story, Aeneas in Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and Bénédict in Berlioz’ Béatrice et Bénédict, all with Eugene Opera, Ferrando in Così fan tutte with City Opera Bellevue, the Chevalier in Dialogues des Carmélites with Vashon Opera, and Tamino in Die Zauberflöte with the Berlin Opera Academy. Mr. Tuohy completed his academic training at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music with a master’s degree in vocal performance. In 2008, he competed in the Metropolitan Opera National Council Semi-Finals in New York City. Learn more: brendan-tuohy.com

Baritone Ryan Bede made his Seattle Opera solo debut in May 2017 as the Second Priest in The Magic Flute, followed by Prince Yamadori in Madama Butterfly, Jim Crowley in An American Dream and Fiorello in The Barber Of Seville during the 2017–2018 season. He returns as Moralés in Carmen in May 2019. Other recent performances include engagements with Opera Idaho, Coeur d’Alene Opera and Tacoma Opera, as well as Spectrum Dance Theater’s acclaimed production of Carmina Burana and Bach’s Christmas Oratorio with Early Music Vancouver/Pacific Musicworks. He has been a frequent soloist with OSSCS in such masterpieces as Fauré’s Requiem, Duruflé’s Requiem and Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on Christmas Carols. Learn more: ryanbede.com/

Program Notes

William C. White

Acadia Fanfare

William Coleman White was born August 16, 1983, in Bethesda, Maryland. He composed this work from February through April of 2016 on a commission from the Pierre Monteux School with support from the Maine Arts Commission to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of Acadia National Park. The composer conducted the first performance in Hancock, Maine, on July 17, 2016. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds (plus piccolo), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion and strings.

This evening’s concert opens with an introduction to OSSCS music director as both composer and conductor. In fact, he found his way to the podium as a result of his early efforts writing orchestral music. “After I had begun to compose in high school,” he recalls, “I was shocked — shocked — to find out that experienced conductors weren’t champing at the bit to perform the works of random 15-year-old kids.” To date his oeuvre includes numerous liturgical choral works (from an a cappella setting of the Nunc Dimittis to a large-scale oratorio, Thy King Cometh), two film scores, much chamber music, and a three-movement symphony (composed for the Cincinnati Symphony Youth Orchestra).

“Acadia Fanfare” writes its composer, “was inspired by the natural beauty of and rugged landscape of Acadia National Park, and also by the musical tradition of the Pierre Monteux School, which sits in close proximity to the park itself. The work opens with a depiction of waves beating against the rocky shores of Mount Desert Island, musically, an homage to Debussy’s La Mer. The squalls of seabirds sound in the distance as the day comes alive. The waves grow larger and larger as the musical texture builds to a breaking point, and finally the fanfare theme itself bursts forth in a blinding array of light and mist. The central section captures the magic and majesty of the park’s interior, and gives the forest birds a turn to speak. The work concludes by once again evoking the rocky coastal shores of Acadia, as an accretion of birdsong and crashing waves usher in a recapitulation of the fanfare theme leading the work to its triumphant finale.”

Lili Boulanger

Psaume XXIV

Marie-Juliette Olga (“Lili”) Boulanger was born August 21, 1893, in Paris, and died at Mézy-sur-Seine on March 15, 1918. She composed this setting of Psalm 24 in Rome during 1916, scoring the choral accompaniment for 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 4 trombones, tuba, timpani, harp and organ.

As a result of her winning the Prix de Rome in 1913, Lili Boulanger was awarded an extended stay at the Villa Medici in Rome (along with a monthly stipend), but illness cut short her initial trip to Italy. Health issues and her efforts in support of students from the Paris Conservatoire fighting in World War I curtailed her composing efforts for a time, but during the first half of 1916 she was able to return to Rome, where she composed settings of Psalm 24 (heard this evening) and Psalm 129 (to be performed by OSSCS in February). She completed a treatment of Psalm 130 (Du fond de l’abîme, which OSSCS listeners will hear in March) the following year.

Boulanger began sketching Du fond de l’abîme as early as 1913, and she may have been contemplating her other psalm settings simultaneously (including several that were never realized). She apparently never heard Psalm 24 performed during her lifetime. Published in 1924, details of its first performance remain elusive.

Dedicated to Jules Griset, an industrialist director of Choral Guillot de Saint-Brice, Psalm 24 opens with fanfares that call to mind the brilliant brass writing of Leoš Janáček’s Sinfonietta (composed a decade later). The scoring for brass, organ and harp suggests, as Boulanger biographer Léonie Rosenstiel notes, “a consciously archaic and regal style,” as does the Gregorian chant–style choral writing for male voices at the beginning of the work. The mood relaxes somewhat at the second verse, with a solo tenor singing the third.

“This is an assertive work,” Rosenstiel continues. “Both the instruments and the voices are quite aggressive in declaring God’s dominion over the earth. The women’s voices appear to add both greater substance and a degree of word-painting to the composition, entering as they do for the first time on the words ‘Gates, lift up your heads, eternal gates.’” The closing pages return to the work’s opening material.

“Whereas the compositions written around the time of her Prix de Rome were impressionistic, characterized by polyharmonics, mixed sonorities, modal and whole-tone scales, and nature poetry” writes Michael Alber, “Boulanger developed a completely different and bold expressivity in Psalm 24.”

Aaron Copland

Suite from Appalachian Spring

Copland was born in Brooklyn on November 14, 1900, and died in North Tarrytown, New York, on December 2, 1990. He composed the ballet Appalachian Spring during 1943 and 1944, scoring it for 13 instruments. After the premiere in Washington, D.C., on October 30, 1944, he condensed the half-hour work and expanded the orchestration to include pairs of woodwinds (with one flute doubling piccolo), horns, trumpets and trombones, timpani, percussion, harp, piano and strings. Arthur Rodzinski conducted the New York Philharmonic in the first performance of this suite on October 4, 1945, at Carnegie Hall.

Had she achieved nothing more during her long life than championing the music of her sister Lili, we would owe Nadia Boulanger a profound debt of gratitude. But she was also a composer in her own right and, perhaps more importantly, the single most influential composition teacher of the 20th century. Her students included Easley Blackwood (the composition teacher of William White), Elliott Carter, David Diamond, Philip Glass, Roy Harris, Walter Piston and Virgil Thomson, plus Burt Bacharach and Quincy Jones — and those are just some of the well-known American composers who benefited from her tutelage.

Undoubtedly the most famous Boulanger student was Aaron Copland, who studied with her for three years during the early 1920s. She “could always find the weak spot in a place you suspected was weak,” Copland recalled. “She could also tell you why it weak.” He described Boulanger as an “intellectual Amazon [who] is not only professor at the Conservatoire, is not only familiar with all music from Bach to Stravinsky, but is prepared for anything worse in the way of dissonance.”

Dissonance abounded in Copland’s music upon his return to the United States. After the January 1925 premiere of his Symphony for Organ and Orchestra (on a concert that also included the first American performance of Lili Boulanger’s Pour les funérailles d’un soldat), conductor Walter Damrosch famously told the audience, “If a young man can write a piece like that at the age of 24, in five years he will be ready to commit murder!”

“Composers differ greatly in their ideas about how American you ought to sound,” Copland said in 1985. “The main thing, of course, is to write music that you feel is great and that everybody wants to hear. But I had studied in France, where the composers were all distinctively French; it was their manner of composing. We had nothing like that here, and so it became important to me to try to establish a naturally American strain of so-called serious music.”

His first efforts in that direction involved incorporating jazz elements into works such as Music for the Theater and his piano concerto, but the four Mexican folk songs he wove into El Salón México, premiered in 1937, marked the beginning of his populist phase, which continued with the 1938 ballet Billy the Kid (making use of authentic cowboy songs) and his film score for Our Town (1944). Copland’s Americana style reached its apex with Appalachian Spring.

“The music of the ballet takes as its point of departure the personality of Martha Graham,” Copland wrote shortly after the work’s premiere. “I have long been an admirer of Miss Graham’s work. She, in turn, must have felt a certain affinity for my music because in 1931 she chose my Piano Variations as background for a dance composition entitled Dithyramb. I remember my astonishment, after playing the Variations for the first time at a concert of the League of Composers, when Miss Graham told me she intended to use the composition for dance treatment. Surely only an artist with a close affinity for my work could have visualized dance material in so rhythmically complex and aesthetically abstruse a composition. I might add, as further testimony, that Miss Graham’s Dithyramb was considered by public and critics to be just as complex and abstruse as my music.

“Ever since then, at long intervals, Miss Graham and I planned to collaborate on a stage work. Nothing might have come of our intentions if it were not for the lucky chance that brought Mrs. Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge to a Graham performance for the first time early in 1942. With typical energy, Mrs. Coolidge translated her enthusiasm into action. She invited Martha Graham to create three new ballets for the 1943 annual fall festival of the Coolidge Foundation in Washington, and commissioned three composers — Paul Hindemith, Darius Milhaud and myself — to compose scores especially for the occasion.

“After considerable delay Miss Graham sent me an untitled script. I suggested certain changes to which she made no serious objections. The premiere performance took place in Washington a year later than originally planned — in October 1944. Needless to say, Mrs. Coolidge sat in her customary seat in the first row, an unusually interested spectator. (She was celebrating her 80th birthday that night.)

“The title Appalachian Spring was chosen by Miss Graham. She borrowed it from … one of Hart Crane’s poems, though the ballet bears no relation to the text of the poem itself.” In fact, Copland had little knowledge of the ballet’s plot until he arrived in the nation’s capital for the dress rehearsal. (It was not unusual for Graham to modify the action of her ballets as she refined the choreography and rehearsed with her fellow dancers.)

Graham described the story as “a pioneer celebration in spring around a newly built farmhouse in the Pennsylvania hills in the early part of the last century. The bride-to-be and the young farmer-husband enact the emotions, joyful and apprehensive, their new domestic partnership invites. An older neighbor suggests now and then the rocky confidence of experience. A revivalist and his followers remind the new householders of the strange and terrible aspects of human fate. At the end the couple are left quiet and strong in their new house.”

The ballet was an immediate success — and so was Copland’s score, which won him the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for Music. Due to the limited space, Copland had scored the work for 13 instruments: flute, clarinet, bassoon, piano and strings. He subsequently set about creating a suite for a standard-sized orchestra, “a condensed version of the ballet, retaining all essential features but omitting those sections in which the interest is primarily choreographic.” For its premiere by the New York Philharmonic in October 1945, Copland provided the following outline of the suite:

- Very slowly Introduction of the characters, one by one, in a suffused light.

- Fast Sudden burst of unison strings in A-major arpeggios starts the action. A sentiment both elated and religious gives the keynote to this scene.

- Moderate Duo for the Bride and her Intended — scene of tenderness and passion.

- Quite fast The Revivalist and his flock. Folksy feelings — suggestions of square dances and country fiddlers.

- Still faster Solo dance of the Bride — Presentiment of motherhood. Extremes of joy and fear and wonder.

- Very slow (as at first) Transition scenes reminiscent of the introduction.

- Calm and flowing Scenes of daily activity for the Bride and her Farmer-husband. There are five variations on a Shaker theme. The theme — sung by a solo clarinet — was taken from a collection of Shaker melodies compiled by Edward D. Andrews, and published under the title The Gift to Be Simple. The melody I borrowed and used almost literally is called “Simple Gifts.” It has this text:

’Tis the gift to be simple,

’Tis the gift to be free,

’Tis the gift to come down

Where we ought to be.

And when we find ourselves

In the place just right

’T will be in the valley

Of love and delight.

When true simplicity is gain’d,

To bow and to bend we shan’t be asham’d.

To turn, turn will be our delight,

’Till by turning, turning we come round right. - Moderate (Coda) The Bride takes her place among her neighbors. At the end the couple are left “quiet and strong in their new house.” Muted strings intone a hushed, prayer-like passage. We hear a last echo of the principal theme sung by a flute and solo violin. The close is reminiscent of the opening music.

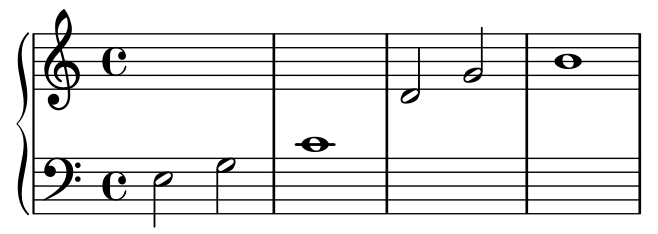

“In 1987,” conductor Leonard Slatkin remarked before a 2014 Detroit Symphony performance of Appalachian Spring, “several people went to visit Aaron Copland at his home in Peekskill, New York. … At this point, Copland was in the severe stages of Alzheimer’s disease. He would die a little over two years later, but he was unable to communicate verbally. Nonetheless, this group, as well as others, were constantly visiting, telling stories, talking about his music — about his influence and importance in this country. On that day, Copland suddenly rose out of his chair and he walked over to the piano, and he played these six notes:

“Those notes, those two chords, form the basis of Appalachian Spring. They’re heard at the beginning, throughout, and those chords are the last we hear in this piece. What was Copland trying to communicate? Perhaps it was simply to tell everyone he was still here. Or perhaps he was saying, ‘This is what I want you to remember of me.’”

Franz Joseph Haydn

“Herbst” from Die Jahreszeiten, Hob. XXI:3

Haydn was born in Rohrau, Lower Austria, on March 31, 1732, and died in Vienna on May 31, 1809. He began work on his oratorio The Seasons in 1799, completing it in 1801 and conducting the first performance on April 24 of that year. In addition to chorus and soprano, tenor and baritone soloists, the “Autumn” section calls for pairs of woodwinds, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, percussion, continuo and strings.

From 1762 until 1790, Franz Joseph Haydn served as kapellmeister to Prince Nicholas I of Esterházy, primarily at his Eszterháza palace 100 km southeast of Vienna. Upon the death of Nicholas, his successor reduced the size of the court orchestra (along with Haydn’s salary), but allowed the composer to travel abroad. At the behest of the impresario Johann Peter Salomon, Haydn made two lengthy visits (during 1791–1792 and 1794–1795) to England, where his music was exceedingly popular.

In London (where he composed some of the most famous of his hundred-plus symphonies), Haydn attended a Handel festival at Westminster Abbey. Haydn had first been introduced to Handel’s oratorios by Baron Gottfried van Swieten during the 1780s, but upon hearing Messiah in London he called Handel “the master of us all” and later proclaimed he felt “as if I had been put back to the beginning of my studies and had known nothing at that point.”

Before leaving England, Haydn received an anonymous libretto adapted from Genesis that had purportedly been intended for Handel. Back in Vienna, he entrusted van Swieten to adapt the libretto into a German text suitable for a grand oratorio in the style of Handel, resulting in one of Haydn’s greatest masterpieces, The Creation. Baron van Swieten subsequently pressured Haydn to tackle another oratorio, this one loosely based on The Seasons, an epic blank-verse poem by Englishman James Thomson. In four parts (one for each season), Die Jahreszeiten mixes choruses and ensemble numbers with recitatives and arias for bass, soprano and tenor in the roles of characters (invented by van Swieten) named Simon (a farmer), Hanne (his daughter) and Lukas (her suitor).

Haydn repeatedly expressed his displeasure with van Swieten’s libretto, along with some of the baron’s suggested tone-painting, particularly the “wretched idea” to depict croaking frogs near the end of the “Summer” segment: “This whole passage, with its imitation of the frogs, was not my idea: I was forced to write this Frenchified trash.” When van Swieten insisted upon translating his text into French and English himself, the results were rather unfortunate and may explain the cooler reception given The Seasons in non–German-speaking countries.

The first (private) performances of The Seasons took place in Vienna on April 24 and 27, and May 1, 1801, at palace of Prince Johann Joseph Nepomuk Schwarzenberg (where The Creation had premiered in 1798). “Silent devotion, astonishment and loud enthusiasm relieved one another with the listeners,” wrote future Haydn biographer Georg August Griesinger in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, “for the most powerful penetration of colossal ideas, the immeasurable quantity of happy ideas surprised and overpowered even the most daring of imaginations. … From the beginning to the end, the spirit is swept along by emotions that range from the commonplace to the most sublime.” The empress Maria Theresa sang the soprano parts in back-to-back performances of The Seasons and The Creation at the Hofburg palace on May 24 and 25. The first public performance of The Seasons followed on May 29 at the Redoutensaal theater.

Haydn was a year short of his 70th birthday when The Seasons premiered. He would live another eight years, but the oratorio would be his last major work: he blamed his toils on The Seasons for “a weakness that grew ever greater.” Nevertheless, Carl Friedrich Zelter wrote to Haydn, “Your Seasons is a work youthful in power and old in mastery.” And Michael Steinberg asserts that it “ensure[s] Haydn’s premiere place with Titian, Michelangelo and Turner, Mann and Goethe, Verdi and Stravinsky, as one of the rare artists to whom old age brings the gift of ever bolder invention.”

Each section of The Seasons opens with a brief instrumental overture. A graceful minuet evoking “the peasant’s joyful feeling about the rich harvest” introduces the “Autumn” segment and leads directly to a recitative for Hanne. She joins Lukas and Simon in extolling the virtues of industry. (Haydn, in one of his frequent jabs at van Swieten, professed that he had “been an industrious man all his life but it had never occurred to him to set industry to music.”) The full chorus joins the trio in a vigorous (and quite industrious) fugue.

Hanne and Lukas then engage in a lengthy love duet that exemplifies the influence of Singspiel (a popular form of German folk opera, the most famous example of which is Mozart’s The Magic Flute) on Haydn’s musical approach. Simon’s ensuing aria features a bassoon obbligato that depicts his hunting dogs tracking the scent of some avian prey. The tempo accelerates, pulls back, and presses forward again (listen for the gunshot). Lukas’ accompanied recitative, describing a hare hunt in quite graphic terms, gives way to a thrilling hunting chorus that, as Steinberg notes, displays Haydn’s “wonderful art of continuously unfolding and surprising variation. Beginning in D but ending in E♭, it also revels in the reckless abandoning of the Classical harmonic tradition. All those hunting calls, blared lustily by four horns in unison, are real ones!”

A recitative for Hanne leads to the final scene of “Autumn,” which critic Karl Schumann described as “a feast of Bacchus in the Burgenland, painted by a musical Breughel.” As the countryfolk celebrate the harvest and drink the plentiful wine, they engage in a “drunken fugue” that David Humphreys calls ”a riotous fugal chorus in which the voices drop the subject halfway through the entries (as in a drunken stupor) while the accompanying instruments are left to complete it.”

— Jeff Eldridge